Get Hitched

Before minivans and SUVs,

families hit the open highway in travel trailers. How one wayfarer rediscovered

their lost allure, stumbled on a tribe of true believers, and decided to take

the road less traveled

By

Mary Melton

4/1/2002

Photograph by Dave Lauridsen

Photograph by Dave Lauridsen

I

met my fate on a Friday at dusk. It was in an RV campground above Santa Cruz, a

place fragrant with redwoods. He was stocky and energetic, with thick brown

hair and a predilection for long denim shorts and hiking boots. He later

described himself to me as "a Ritalin child" who battled addiction as

a young man, got sober, and was born again. After spending time with him, I

surmised that he may have been born again twice—once in the name of the Lord,

and once more in the name of travel trailers.

His

name was Craig Dorsey. Behind him, nestled among towering trees, gleamed his

latest project, a 1953 Southland Runabout. Formerly a commercial art director,

he had turned his weekend hobby—restoring vintage travel trailers—into his

livelihood. This was a safe bet after it took him less than an hour at a Pomona

car swap meet to sell his first baby, a 1956 Mercury 14-footer with Formica

countertops. He told me how he paid $250 for a '46 Spartan Manor full of nudie

magazines and ten gallons of rat droppings, then rebuilt it into a

mahogany-paneled movie-star palace. He recalled how tough it had been to let go

of that exquisite '51 Spartanette with whom he'd shared 700 painstaking hours

of toil and trouble. He explained how it could take days to scrape off green

house paint, which looked like it had been applied with a broom, to reveal a

metal finish. He had the tan of someone who had spent too much time polishing

reflective aluminum under a harsh sun.

"You

want to see inside the Indian?" he asked. Sure, I said. I walked through

the portal and haven't looked back since.

Travel

trailers are those rolling homes-away-from-home, usually made of aluminum or

wood, that hitch to a car or truck. I'd seen my share of them during jaunts in

the desert or off lonely train routes while I zoned out on Amtrak. Although I

live in a 1950s house and am enamored with camping and the outdoors, I never

gave them much thought. The old ones looked shabby, and the new ones monstrous.

I didn't know anything about their history, that during their heyday, the '30s

to the '50s, thousands of different trailer models roamed the highways. That,

encouraged by our ideal climate and ties to aerospace, many were manufactured

in Los Angeles. The travel trailer had been a potent symbol of Southern

California's mobility and adventurous spirit.

And

if a core group of fanatics based here has anything to say about it, perhaps it

will be again. I discovered this when I stumbled onto the Web site for Vintage

Vacations, the travel trailer restoration workshop in Santa Ana run by Dorsey.

When I called him on a whim, he invited me to experience one of his new

acquisitions, a 1940 Indian, at an upcoming rally.

Had

nothing changed in this trailer since FDR gave fireside chats over the radio?

The linoleum floor was original, as was the scratchy mauve couch with matching

toss pillow. The quality of the workmanship on the bentwood paneling was

astounding. I played with the screen-door latch, sat at the dainty vanity. I

closely examined the closets and pictured the gabardine shirts that once hung

inside. I peered into the petite icebox, placing my hand on the cool metal. I

opened the pantry, expecting a Moon Pie to emerge. I clicked the reading lamp

on and off, bathing in its glow. It was ship cabin and Pullman car and mountain

retreat rolled into one. I was in love.

I

was also sleepy. I used my wool jacket as a blanket, but it was the golden

walls that enveloped me that brisk night.

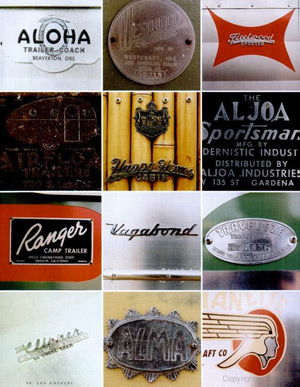

Early

the next morning I wandered the campground, passing row after row of pre-1960

trailers. I fell for the metal identification tags on their sides, with names

like the Traveleze and Rod and Reel, the Vagabond and Gypsy Coach. From their

windows emanated soft clouds of warm light. The rally goers were waking up in a

forest under their own roofs, with their preferred coffee on the stove and

flapjacks on the griddle. They were unfolding vintage canvas chairs and rolling

out striped awnings; they were throwing checkered cloths over picnic tables and

unpacking Bakelite flatware.

Across

the grove was John Agnew, a Teamster from Highland Park, in his 1954 Silver

Streak Clipper, and Phil Noyes, a producer from Mid Wilshire, in his 1957

Corvette. There was a retired hand surgeon in a '35 Bowlus Papoose, one of four

in the world, and a car collector with a home-built trailer that came with a

scrapbook showing the honeymooning couple who had taken it to Niagara Falls in

1936.

The

trailerites, about the swellest bunch of people I'd ever met, taught me about

the hard-to-find wood models from the 1930s and the easier-to-find flat-sided

tin ones from the '50s, called "canned hams," that you could pick up

in the Recycler for 300 bucks. They traded polishing techniques and towing

disaster tales, ate potluck and watched Lucy and Desi in The Long, Long Trailer

as the film seeped through the bedsheet screen onto the shiny surface of

Dorsey's Southland Runabout. By Sunday morning, I must have looked vulnerable.

"So,"

Agnew asked me, "when are you going to step up to the plate?"

AMERICANS

BEGAN STEPPING UP TO THE plate—that is, buying travel trailers—in the '30s.

Before that, campers visiting our new national park system were likely to sleep

in canvas A-frames or primitive pop-up tent trailers. The itinerant population

looking for work during the Depression fabricated crude homes-on-wheels using

salvaged plywood and truck chassis. We began to crave leisure just as a

burgeoning airplane industry was shaping metals into the most aerodynamic forms

possible. Taking cues from planes, travel trailers evolved from wood

contraptions into riveted aluminum bullets—would that they moved that fast.

One

of the industry's early innovators was glider designer William Hawley Bowlus.

He had been the plant manager at Ryan Aircraft when the San Diego company built

the Spirit of St. Louis. In 1934, at his Bowlus-Teller Trailer Company in San

Fernando, he devised a tapered, aluminum-framed tube wrapped in a skin of

lightweight alloy. Before "trailer trash" became an unfortunate part

of our vernacular, he made expensive toys—a basic model started at around

$1,050—aimed at the wealthy.

Too

expensive, perhaps. Bowlus overspent on fancy materials and went bankrupt. One

of his salesmen, Wally Byam, took over production. Byam was a showman, and he

called his company Airstream because the trailers rode "like a stream of

air." Byam's first mass-manufactured trailer, the Airstream Clipper,

charged out of a brick factory in Van Nuys in 1936. "Man, it sure did look

a lot like the 1935 Bowlus Road Chief," write Bryan Burkhart and David

Hunt in their 2000 history Airstream.

Byam

led trips around the world. Airstream owners formed Wally Byam Caravan Clubs,

with members wearing blue berets adorned with patches bearing his mug. Though

Airstreams were the most visible travel trailers out there, and rightly

heralded for their iconic design, hundreds of other manufacturers filled

tourist camps—by 1940 there were 35,000 such places in the United States—with

their own visions. A surplus of airplane materials after World War II led

trailer companies to open in El Monte, Long Beach, Cypress, Gardena, Sun

Valley, and elsewhere. In 1950 John and Donna Crean of Compton began selling

venetian blinds for travel trailers through their California Coach Specialties

Company; in 1964 they changed the name to Fleetwood, and it is now the largest

recreational vehicle manufacturer in the world. Travel trailers would peter out

by the '70s, a little too "mountain cabin" when consumers wanted something

more "three bedrooms and a satellite dish." Of the 300 trailer

companies that operated in 1936, only Airstream has survived.

There

has been lots of talk in recent years about the rediscovery of Airstreams, how

collectors in Japan and celebrities like Tom Hanks, Sean Penn, and Tim Burton

covet them—and inflate their value. MTV put one in the lobby of its Santa

Monica headquarters; chef Fred Eric is opening the Airstream Diner in Beverly

Hills in April. Hard-core trailerites would never say it out loud in a

campground full of Wally Byam fanatics, but many find the Airstream played out,

even a little gauche. I've heard one go so far as to say that Airstreams are to

trailers what condos are to castles. They're too cookie-cutter. Their aluminum

interiors are too cold—the exact quote is "butt ugly"—when compared

with the cozy woods of their bygone competitors. Where's the sense of

discovery? The neglected treasures—those are the mysteries. They hide out, in

weeds behind beauty salons, on the fringes of Kmart parking lots, under freeway

overpasses. A 16-foot 1963 Airstream Bambi might set you back $14,000. On the

other hand, you can spy a 14-foot 1963 Shasta behind a cinder-block wall and

knock on the house's front door, only to be told, "Take it, just get that

thing out of my backyard."

I've

been chatting with travel trailer owners for a while now, and have determined a

few things: They tend to be men in their late thirties who were car collectors

in their twenties. They are handy with a jigsaw and relate to propane tanks.

Like truckers on CBs, they know each other's eBay handles; they don't hold much

of a grudge when a pal outbids them on a 1948 Trailer Topics magazine or an

original Spartan sales brochure. They have understanding neighbors. Some own only

one and call it ah, my dream trailer, while others own a few dozen and have yet

to find Mr. Right. When they chug a trailer up an incline, they're never sure

if the car passing on the left is going to give them a thumbs up or the finger.

Trailers

signaled leisure and wanderlust. If it was the American dream to own a home,

then how cool was it that you could own a home in which you could see America?

Transcontinental roads were new in the '30s, and people were unafraid to pull

over and ask a farmer if it would be all right to camp out for the night.

"Home is where you stop," said Wally Byam.

Trailers

may remind us not of those fabled good old days, which were so bad for so many,

but of something else. "They are just so cocoony, womby, engulfing,"

says David Wilson, the founder of the Museum of Jurassic Technology, as he sits

in his parking lot office, a splendid 34-foot 1951 Spartanette. Maybe that's

it: Travel trailers provide us with something that we've been missing since the

day we were born.

IT'S

CALLED "THE GLOW," THE BUZZ OF LIGHT thrown by honey-colored wood

that radiates from travel trailer windows. "It's unlike any other

light," says Phil Noyes, who cowrote an upcoming book, Trailer Travel: A

Visual History of Mobile America, and is producing a PBS documentary on the

subject. "That glow makes you want to be around them and in them."

I

experience the glow again at the next year's rally, held at a campground in

Newport Beach. (This year's will also be at the Newport Dunes Resort, from May

16 to 19.) I meander the aisles by day, bewitched by a 1953 Happy Home

transformed by its owner, a surfer and personal trainer, into a tiki

wonderland. There are many friendly faces from the previous get-together, but

there are also some strangers.

Tourists

and looky-loos are roaming around. I suppose this is Craig Dorsey's hope—to

garner interest and raise the profile—but some of the trailerites are

grumbling. They fear they might get boxed out by the well-heeled

Johnny-come-latelies. They point to Roseanne, for instance, who is overheard

making an offer (of $11,000, to no avail) on the tiki trailer.

Saturday

night, my husband and I visit with Phil and John and their pals Steve and Ed

outside John's lovely Westcraft. We sit around a campfire on '40s rattan

furniture. John's girlfriend, Yipsy, is mixing chi-chis in the kitchen. The

guys are chatting about cherry trailers they'd seen that day and a few that

were not ("I don't think he's ever going to get that cat smell out of

there"). They're not thrilled with the remodels bursting with Betty Boop

and Route 66 kitsch, but as John puts it, "There's room for

everybody." Working full-time, they lament, means that they rarely can

enjoy camping like this. The guys would have more time if they weren't always

buying and selling trailers, I needle them.

‘As

for those good old days, "there's no better time than now," says

John, who is black. "In the '40s, I wouldn't be polishing my trailer, I'd

be polishing your trailer. I wouldn't be kicking back having cocktails with a

pretty Mexican girl by my side, hanging out with a bunch of white guys in a

campground." A few drinks later, I'm beat. I don't have a trailer to sleep

in this year, so we bid them good night. As we walk through the hushed

campground, the glow is intoxicating.

We

are staying at a Best Western on Pacific Coast Highway. The $89-a-night room is

at street level, and the traffic appalling. It is prom night in Newport Beach,

and about a dozen drunken seniors party in adjoining rooms until dawn. The

mattress, the pillow, the bedspread—the horror. The front desk is

unsympathetic. Our complimentary breakfast consists of stale Danish and nasty

coffee. This is no cocoon, it's a flame-retardant mausoleum. The glow! How I

yearn for the glow!

A

few months later, while driving across the Mojave, my husband and I glimpse a

travel trailer parked behind a junk shop. We screech to a halt. I've never

heard of the model: a 1950 Glider, made in Chicago, with a tag that proclaims

it "Graceful as a Bird in Flight." It is a beauty. A woman named

Betty Sue has called it her desert home for the last 40 years, and no offense,

gentlemen, it shows: The inside is spotless, with birch cabinetry, a little

Dixie stove, and an icebox. A back bedroom closes off with a sliding door, and

there is even a tidy bathroom stall with a showerhead and a mint-green

toothbrush holder. It needs a couple of new windows and a paint job. They want

$2,000 for it, but we think we can talk them down to fifteen. We have no idea

where we'll put it, or even how we'll get it home. But none of that matters

now.

It

is time to step up to the plate.